The walls whisper stories of lives forgotten, of hands once steady now trembling with age. Inside Japan’s largest women’s prison, time does not stand still. It marches on, indifferent to the weight of sorrow. The corridors echo with the shuffling of elderly feet, slow and measured as if each step is a quiet plea to be remembered. Wrinkled hands clutch onto the few possessions they have, but what they crave most is something intangible.

Dignity, warmth, a place to belong.

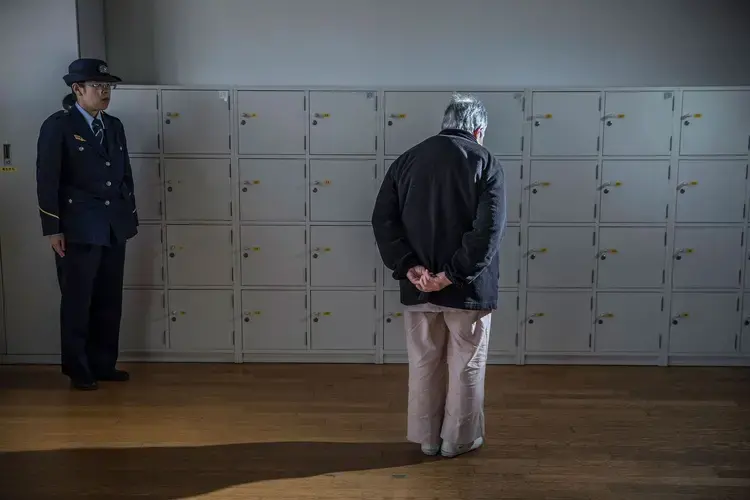

This is not a nursing home. This is a prison where elderly women find a strange sense of refuge, a place where loneliness is dulled by the structured routine of incarceration. It is a paradox too cruel to ignore: outside these walls, they are abandoned, struggling with poverty and isolation. Inside, they find stability, even companionship. Some have come back willingly, breaking laws just to return to a place that, ironically, feels more like home than the world outside.

For some, prison is not just a punishment. It is a refuge.

A Life More Stable Behind Bars

Imagine reaching your later years, not surrounded by family, but in a small prison cell. That is the reality for many elderly in Japan. At Tochigi Women’s Prison, where one in five inmates is over 65, women like Akiyo, 81, find themselves behind bars not because of violent crimes, but because of shoplifting food.

Source: Getty Images

Akiyo is not alone. Many elderly inmates in Japan return to prison not out of malice, but out of desperation. Inside, they are fed, given medical care, and surrounded by people. Outside, they face isolation, financial hardship, and a society that often has no place for them. Akiyo describes prison as the most stable life she has ever known.

When Poverty and Isolation Lead to Crime

Shoplifting is the most common crime among elderly women in Japan. In 2022, over 80% of elderly female inmates were jailed for stealing. Some do it to survive, with 20% of Japan’s senior citizens living in poverty. Others do it because they have nothing left to hold onto.

Akiyo’s story is heartbreakingly familiar. Living on a small pension that came only every two months, she struggled to make ends meet. With just $40 left and two weeks until her next payment, she made a desperate choice—she stole food. That act landed her back in prison, where, despite the loss of freedom, she found a strange sense of relief.

On the outside, she had no support. Her own son, now in his 40s, had once told her, “I wish you’d just go away.” Those words cut deeper than any prison sentence ever could.

Prison as a Last Resort

In Japan, prison has become a safety net for the elderly. Some deliberately re-offend just to return. Yoko, 51, has been in and out of prison for 25 years on drug-related charges. She has seen the prison population age with each return.

Some elderly inmates, knowing they will struggle to afford food and healthcare outside, prefer to remain incarcerated. In prison, they receive free meals, medical treatment, and the companionship that is missing in their lives outside. Some would even be willing to pay to stay behind bars permanently.

The Cycle of Shoplifting and Incarceration

Names have been changed for privacy, but their stories reveal a stark reality—one where a life behind bars feels safer than freedom.

Source: Shiho Fukada

The first time Ms. F was sent to prison, she was 84 years old. She had stolen rice, strawberries, and cold medicine—not out of desperation, but as a quiet plea for a life she no longer had outside. Now, at 89, she is serving her second term. She is not alone.

Across Japan, a growing number of elderly women are finding solace behind prison walls. For many, incarceration is not a punishment but a refuge. A structured life, three meals a day, and companionship are luxuries that the outside world no longer provides. In a society that once prided itself on filial piety, these women have been left behind, forced to seek security in the unlikeliest of places.

Japan’s Forgotten Grandmothers

In 2016, Japan’s parliament passed a law aiming to help recidivist seniors by connecting them with welfare and social services. But while the legal system has adapted, the root causes of this crisis remain untouched. Loneliness, poverty, and an overwhelming sense of purposelessness drive these elderly women to commit petty crimes—over and over again.

Ms. A, 67, was not in financial need when she shoplifted over 20 times.

Source: Shiho Fukada

She stole clothing—not expensive items, just simple pieces on sale. The thrill of getting away with it filled a void in her life. Her husband supports her, but her sons are ashamed. To her grandchildren, she is simply “in the hospital.”

Ms. T, 80, once spent her days as a diligent worker in a rubber factory and later as a caregiver at a hospital. She was never one to break rules. But when her husband suffered a stroke and developed dementia, she was left to care for him alone.

Source: Shiho Fukada

The weight of his delusions, paranoia, and physical needs crushed her. At 70, she stole for the first time—not because she lacked money, but because she lacked an escape. Prison gave her that.

“I didn’t want to go home, and I had nowhere else to go,” she admits. “Prison was the only place I could ask for help.”

A Life of Solitude, A Home in Prison

For Ms. N, 80, loneliness was unbearable. She had financial security, but it meant nothing without companionship. The first time she stole, it was a simple paperback novel. The police officer who arrested her treated her with kindness, listening to her in a way no one else had. She kept stealing. She kept returning to prison.

She found purpose within its walls, working in the prison factory, thriving under the structure and camaraderie. Each time she was released, she longed for the life she had behind bars. “When I was out, I couldn’t help feeling nostalgic,” she confesses.

Ms. K, 74, and Ms. O, 78, share similar sentiments. Life outside is a constant struggle—rationing welfare money, living on the fringes of society, waiting for a tomorrow that holds no promise. Ms. O calls prison her “oasis,” a place where she can relax, eat, and talk to people. “My daughter says, ‘You’re pathetic.’ I think she’s right.”

A System Overwhelmed by Age

The rise of elderly prisoners has transformed Japan’s prisons. Guards at Tochigi Women’s Prison admit that their job now includes changing diapers, helping inmates bathe, and managing chronic illnesses. What was once a facility for criminals now resembles a care home for the forgotten.

Source: CNN

Prisons were never designed to serve as eldercare facilities, yet that is exactly what they have become. And with Japan’s population crisis worsening, the issue is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

A Society That Needs to Do More

Japan’s ageing population is often discussed in economic terms. Rising healthcare costs, pension burdens, and workforce shortages. But these women’s stories reveal a deeper crisis: the erosion of social ties and the failure of community support systems. They are not hardened criminals; they are mothers and grandmothers who found themselves discarded in a rapidly changing society.

Prison is not an ideal solution, but for many, it is the only one that works. The government may pass laws and introduce welfare initiatives, but as long as loneliness and isolation persist, elderly women will continue to steal their way into the only place that makes them feel seen.

But Japan’s government is aware of the problem. Authorities have introduced early intervention programs, community support centres, and initiatives to provide better housing benefits for the elderly. But is it enough?

The truth is, without strong community support, many elderly people feel they have no choice but to turn to crime. They do not want to steal. They do not want to be arrested. They simply do not want to be alone.

What Can We Learn from Japan’s Elderly Crisis?

As Singaporean parents, this raises an uncomfortable but important question: What kind of future are we creating for our own elderly? The thought of ageing parents or grandparents struggling with loneliness and poverty is heartbreaking. It is a reality we must confront before it is too late.

Do we have systems in place to support our ageing population? Are we fostering intergenerational bonds strong enough to prevent our elderly from feeling abandoned? Do we teach our children the importance of caring for their elders, not just financially but emotionally?

Japan’s crisis is a warning sign. One we should not ignore.

Building a Future Where No One Feels Forgotten

As parents, as caregivers, as human beings, what does this say about the world we are building? If our elders—those who have given so much—are left with no option but to seek comfort behind prison walls, what does that mean for the rest of us?

Perhaps the saddest truth is not that these elderly prisoners feel at home behind bars. But that they feel lost outside of them. These women do not need stricter sentences or harsher deterrents. They need purpose. They need connection. They need a society that acknowledges their struggles before they resort to crime. Until then, Japan’s prisons will remain an unexpected sanctuary. A place where they are not forgotten.

The walls whisper their stories, but will we listen? Or will we wait until it is too late, until we, too, are searching for a place to belong in a world that has moved on without us? When freedom itself feels like a punishment, what does that say about the world outside?

A society is measured by how it treats its most vulnerable. As Japan grapples with its ageing crisis, we have a chance to learn from its struggles and ensure that our elderly never have to choose between freedom and survival.

Because no one—no parent, no grandparent—should ever feel that prison is their best option.

ALSO READ

Caregiving for Elderly Parents: Finding Balance and Support

Teen Duo Delivers Bouquets for Elderly, Spreads Joy in the Community

‘People Here Treat Me Well’: Elderly Woman Travels From Hougang to Yishun Every Day

Together Against RSV

Together Against RSV SG60

SG60 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Parenting

Parenting Child

Child Feeding & Nutrition

Feeding & Nutrition Education

Education Lifestyle

Lifestyle Events

Events Holiday Hub

Holiday Hub Aptamil

Aptamil TAP Recommends

TAP Recommends Shopping

Shopping Press Releases

Press Releases Project Sidekicks

Project Sidekicks Community

Community Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us Contact Us

Contact Us VIP

VIP Rewards

Rewards VIP Parents

VIP Parents